Pianodrome Blog

Piano action in words.

Roundhay Mini-Piano-Shed

The Roundhay piano shed getting its first use

Key notes of a pianodrome journey.

Extract.

The culmination. The mini-shed.

A seed of an idea, the seeds sown, a sedum roof.

From the first meeting with Pianodrome on the seventh floor in Besbrode piano emporium as part of the Leeds Piano Trail planters project, piano magic sparked and trailed and blazed across the city and weaved its mystical way up to Roundhay Primary via a trio of pianos donated to the school by Besbrode's. One for the top playground, one for the Reception class, and the most wonderful setting of all, was for one in the woodland Forest School area.

Tim brilliantly offered ideas as to how to best keep them dry and playable - and in doing so offered to help create a mini-shed for the woodland one. A living shell of protection, growth and nurture. I took a trip to Granton to assist with the build - a day of play - helping choose the wood, colours, style, and learning from all the discussions; angles and joins, living roof/soil weight and wire hanging basket designs.

In the pianodrome setting - anything seems possible. Creativity, energy, music and conversations flow around the warehouse, and folks drop in and out all day involved in various activities or just having a cuppa. It's a delight to be there, and we make really good time on the mini-shed. A return visit of the pianodrome team a few weeks later in the Yorkshire spring sunshine ensued to install the mini-shed.

Surrounded by an excited group of children, distracted by ladybirds and sticks, the shed, made entirely from reclaimed piano wood, started to take shape. Tim's creative vision coming to life, Matt, Tom and Shona creatively supporting; digging required for stone slabs, saws required for adjustments, conversation and answers for endless children's questions. This is their beginning...the adventure of planting and growing on it come next. Little minds whirling.

And coming beautifully in full circle, as the last screw was in, tools tidied away, as the children happily played and experimented, we all took leave, happy hearts, smiling at the shed in the midday sunbeams. We headed back down to the place where it had all started - Besbrode - to share a communal lunch of joy, gratitude and connection.

Thank you Pianodrome.

The children rush to it, marvel at it, play it.

Open it up, teeny hammers plonking, a pink neon felt line, bug hotel holes. Endless hours of fun. The melodies that now flow and tinkle through the woodland at our Forest School sessions create moments of giddiness, delight, joy, companionship, and calm. It's so beautiful to listen to whilst we potter and play outside. Living breathing connections. Wood within a wood. Music for the soul.

Dora Goldsbrough

Forest School Leader

Roundhay Primary, Leeds. Yorkshire.

How did you get that up there?

You may well ask…

Tim and Tom keeping the lid on a container-mounted grand, Granton

You may well ask…

Believe it or not the short answer is; up the ladder.

A slightly longer answer is; this lovely Chappell grand piano came to us from Gillespies High School in Marchmont back in 2015. I had borrowed a van and persuaded my pal Dragon to help me move it down some stairs while the kids were milling around. This was insane. It was way too heavy for us but somehow we managed. Dragon’s kung-fu training really helped. It was our first grand and it sounded great.

The Hidden Door festival was in the Arches by Waverley Station that year and after a wild proto-Pianodrome installation there in which our Chappell held pride of place, we had no means to remove it and nowhere to move it to. We tidied and swept the echoing arch, leaving the grand there in the middle of the empty floor and closed the big wooden doors on it.

Darkness and dust kept the piano company for a year until the developers came. Thankfully they managed to contact me before the piano got chucked in a skip. By happy coincidence Kelburn Castle wanted it and a rustic crew helped hoik it onto a tractor trailor and drive it up to the High Viewpoint there where, on a plinth, under a tent it comanded a spectacular panoramic view of the Firth of Clyde and awaited equally spectacular performances at the imminent summer Garden Party.

A few months earlier, in another tent, this one on a beach and emblasoned with the words ‘Portabello Peoples Piano Project’, I had found another piano with an empty sleeping bag behind it and the music for Beethoven’s Pathetique on the stand. When I had finished stumbling through the second movement I noticed a business card. Ben Treuhaft, Underwater Piano Shop, tuning £35 through 2016. I kept the card. Naturally, later, I thought of Ben to tune our grandly situated grand at Kelburn which he duly did. But I never got to hear what turned out to be the piano’s swan song.

That night, at Kelburn, disaster struck. A storm blew away both the tent and the lid of the piano. Everything was in disarray. When I returned I found Hector of the Chapel Perilous Sound System in the castle kitchen trying to dry out his mixing desk on the Aga. At the High Viewpoint I found the piano in ruins. The strings were submerged and rusting in two inches of rainwater. The amusing irony of Ben’s shop name was small consolation. I was heartbroken. I had cared for this piano. Through the communal efforts to move it and the wonderful music it had played I had become attached to it.

Though I had no idea of the futility at the time I resolved to save it. I carefully removed the action and put it in the boot of my car with the heating on and the windows open to dry it out. I tipped the ponds-worth of rainwater out of the soundboard and limped home. In the Pianodrome container at the Forge I set the piano up in hopes that one day, when it had fully dried out I would be able to bring it back from drowning.

Chappell, drowned in the Pianodrome container.

You know when you have a project which is basically impossible but you don’t want to accept it and so nothing happens for almost ten years? Cue Sophie Joint.

At the beginning of this year, Sophie, a wonderful singer songwriter from Glasgow got in touch to ask if we could bring a grand piano to the beach as a prop for a music video which she was making to coincide with her album launch. We were just moving out of Debenhams to Granton and we had use of a van.

By this point we had more grand pianos than we knew what to do with. One that had graced the glass display cabinet at the front of our derelict department store showroom, a Lunar, we had had to leave behind when we left. I recently searched in vain for it in the lunar landscape of rubble there to no avail.

The moment had come to accept that our Chappell’s playing days were over. We destrung it and walked it, legless and perpendicular on a trolley, half way along Granton Pier over icy and uneven rocks which threatened at any moment to tip it, and us, into the freezing January sea. Sophie finished the shoot, miming soundlessly, seamlessly on the now silent keys and went home to warm up.

Sophie Joint with the silent Chappell on the freezing Granton Pier.

A couple of hours later we swung by with the van to pick up the piano but not before it had garnered significant curiosity. A local walker took a picture of their dog seated at the keyboard and posted it. It went viral and got picked up by the BBC who got hold of my number and interviewed me over the phone. It made The Nine news. Crazy.

Finally, what to do with this beautiful piano carcass? Why not put it on the roof? It doesn’t weigh too much now the harp and strings are out. Why don’t we tie a rope to the front and push it at the back using the ladder as a ramp? Better secure the lid so it doesn’t blow off in the wind.

That’s how we got it up there.

The Blankest of Canvases, Part 2

Fearne and David manning the fort

When I returned to the showroom after a 6 week spell in America the Adopt a Piano scheme had become a more vibey place. Fearne had appeared to play her mesmeric music at the front of the showroom while her dad David invited people in. Jane had found us funding enabling Joel Sanderson and Ben Treuhaft to run fixing and tuning workshops; they imparted revelatory knowledge to us as to which pianos could be saved and which ones were “scrappers”. In June Tom Binns gave a pivotal workshop on how he runs Glasgow Piano City (https://www.glasgowpianocity.org) transforming our fledgling, ad-hoc scheme into a functioning enterprise focused on upgrading pianos before they go back into the wild. More volunteers arrived to help run the project; Alison, Alma, Artem, Davey, Fionn, Georges, Jonny, Kayhan, Laura, Louise, Mirra, Pip and more all helped lift the project off the ground.

A piano saved by the intervention of Louise and Alison

By the end of September we were in full flight and heading for the horizon, that’s when we were given the surprise news that we had one month to vacate the space as it was finally being redeveloped. After setting up and building the project, seeing everyone’s hard work paying off it was difficult to contemplate packing up and trying to start again somewhere else. The windowless, blank void of Debenhams had become a dear home to me; not just because of the showroom days, but all the concerts, piano sharings, magic shows, film screenings, talks and random encounters that had happened there. Furthermore it was also the place where I had found my feet at the Pianodrome, where I had learnt so much and made many friends.

Fionn and me investigating a “bird cage” action

We had just hit the milestone of 100 pianos adopted since opening in January. Our event celebrating this landmark became our closing event for our time at Ocean Terminal. Shona and I worked on a display telling the story of our time there. We had a volunteer showcase in the Pianodrome where Fearne, Louise, Georges and Artem played beautifully, There was a spirited rendition of The Trout Quartet by Tim, Joey, Meg and Chris and a heart warming Piano Sharing to finish.

Shona working on the display, shoppers browsing

We finally moved the last pianos out of Ocean Terminal in January 2024. The electricity had been shut off so we dismantled the Pianodrome in the dusty gloom and coerced the piano cube sculpture down the stationary escalator on a makeshift sledge. Excavators flashed past in the background as we extracted our belongings just in time. As I left what had been the showroom one last time I closed the fire exit door onto the loading bay outside. There was a knack to it that I’d honed through endless practice, giving each half door enough momentum to click into place together, locking me out once and for all.

Everything must go: Tim and Matt dismantling the piano cube before sliding it down the escalator

Recently I wandered over to see the space we once occupied. One year on nothing remains but a pile of rubble and splinters. This time luxury apartments will fill the void for a time. I have to look elsewhere for remnants of our presence there; I have many photos and videos if ever I want to travel back in time. In one video I’m walking through the showroom from the bathrooms at the back. Pianos line the corridor with a couple of punters trying them out, heading to the right we can see the tuning and fixing station; someone is working on a piano on the outer reaches of our orbit. Walking past the sheet music library into the Pianodrome amphitheatre a group of teens are hanging out. Then I follow a family out past the grand piano planters to the front entrance where Georges is playing to his friends and the public at large.

This video shows what can happen when a group of people are allowed to inhabit a space for a while. Given a purpose, community can spring up in the most sterile of environments.

One year on, Adopt a Piano has successfully been transplanted to our headquarters in Granton. Now a couple of mannikins haunt our warehouse reminding us of the time we materialised in an abandoned department store. It’s immensely gratifying that the community which grew there has moved with us too.

Spooky yet reassuring, a momento from our year in O.T

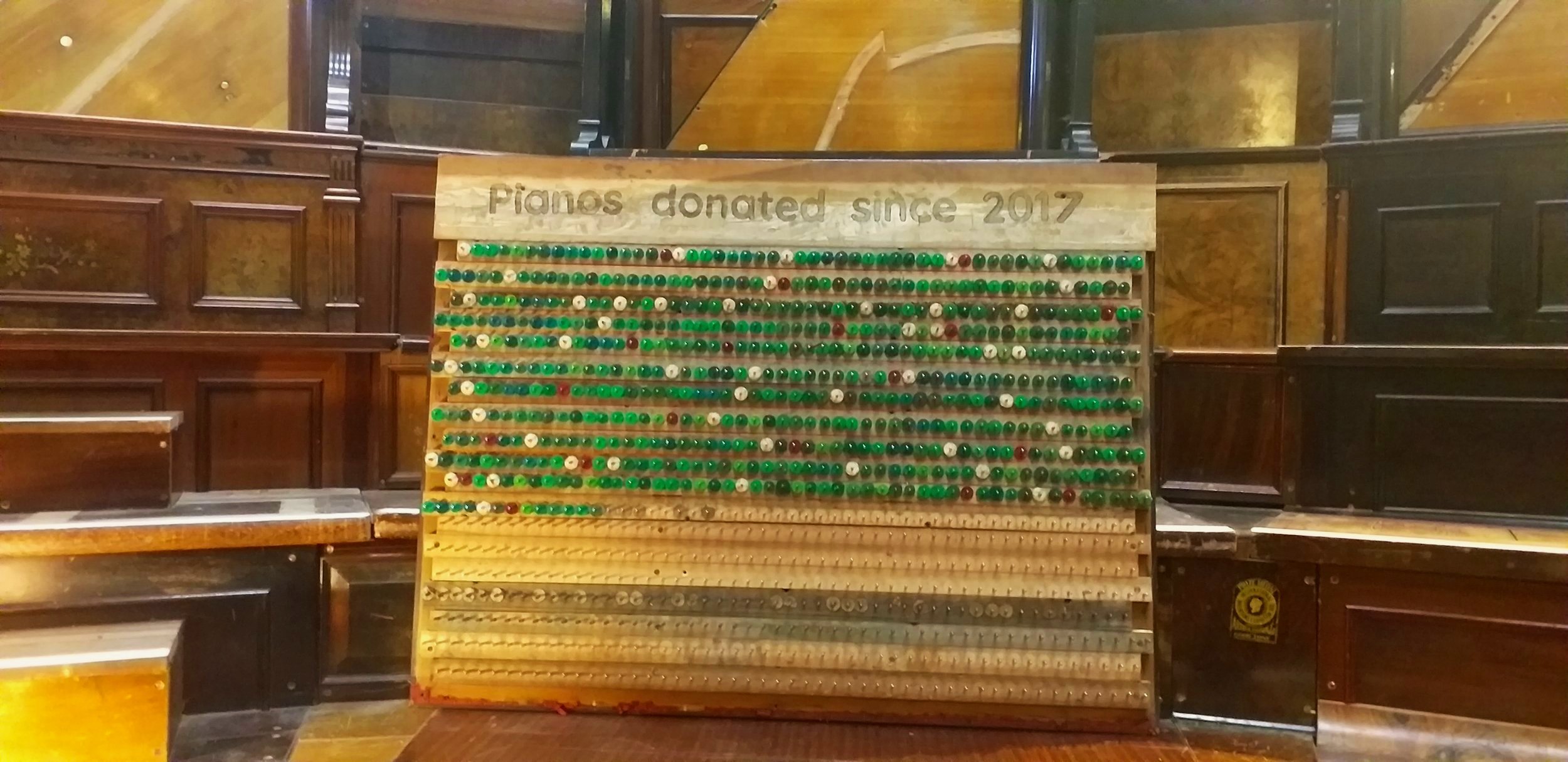

Introducing the Pianometer

Early this year we shot through the landmark figure of 500 pianos donated to the Pianodrome since Tim and Matt started the project in 2017. To recognise the efforts and goodwill of people who have donated pianos to our project and to help visualise the scale of this achievement Georges, Mirra and I have constructed a “Pianometer”.

Using keyboard pin rails to form a grid and felt washers to represent each piano given to us we have created a physical rendering of how many pianos have flowed into Pianodrome.

Once it was made we weren’t sure which way up it should go. Putting the chart vertically highlights its numerical form; the columns fill up satisfyingly from bottom to top, while turning it horizontally makes it read like a narrative; each new washer placed from left to right is another part of the story. We went with the latter, the added benefit being not having to use a small stool to reach the higher pegs.

As of writing, the Pianometer faithfully records that 563 pianos have been donated to the Pianodrome, this is both a very large number for a small organisation such as ours and the tip of the iceberg of pianos floating around the globe. Sadly at present we are unable to take in all the pianos that are offered to us by people in and around Edinburgh. It is an aspiration to serve our community as a home for all pianos which are destined for landfill but currently we do not have the capacity both in resource and space to hold and process all the instruments which are past their play by date.

Of the 563 pianos we’ve received, the majority have gone into our sculpture builds. Over 80 have gone into the making of our two Pianodrome auditoriums, recently three more were added as playable pianos to the Old Royal Pianodrome for our Leeds venture in September 2024. A piano cube sculpture requires six pianos; a half cube three, the piano shed currently based at Middle Meadow Walk, Edinburgh took about three pianos to make plus the one playable inside. Squinting at the 20 foot high Elephant in the Room sculpture from a distance I’d say there’s at least five pianos worth of wood up there plus the three harps on the floor. Most recently two uprights and two grands have been turned into planters for Glasgow school of art and so it goes on as we munch our way through the hundreds of pianos before us. We’re immensely grateful to all the people who’ve pulled apart pianos alongside us.

Plenty of pianos in “The Elephant in the Room”

While the bulk of our work has been turning pianos into sculpture, over 200 pianos have also been rehomed. Many of the pianos received have plenty of life left in them and we’re indebted to all those who have entrusted these pianos to our Adopt-a-piano scheme. By taking the time and effort to donate their pianos to us they both keep real pianos in the world and help the Pianodrome stay afloat financially between projects.

Brinsmead 312 taken for a ride

By cross referencing our paperwork we can use the Pianometer to identify key pianos in our journey and remember pianos which are gone but are not forgotten. Washer 312 signifies a wonderful 19th century “Brinsmead” which has an extremely rare sostenuto pedal for an upright piano. Originally adopted by Meagan it came back to us as it couldn’t fit down the stairs leading to her basement flat. Eight months later it was strapped onto the back of a John Deere utility vehicle and taken down through a forest glen to a cabin in the middle of Tir Na Nog wood where it now resides.

A tree stump piano stool completes the picture

Every washer tells story; number 509 represents a sun bleached “Bechstein” grand piano. It was dropped off one day by Gerry at Edinburgh Piano Moves from a deceased music teacher’s house. Joey, Shona and I spent days totally stripping down and repairing this piano, turning a quirky player into a really good instrument for its new home in Leith. Washer 563; a purple painted “Alison” piano is the latest addition to the chart. Picked up by Tim from Besbrode Pianos in Leeds, Joey and I opened it up on Monday to discover a guinea pig nest inside. Despite this and other more run of the mill drawbacks we’re looking to restore it for a comedy club in town. Or simply just washer 356; “Abbey”, a piano with a lovely tone but some erstwhile moth damage which stayed with us in the showroom for a total of 15 months before finally finding its new home. I could go on…

Alison 563, a nice sounding piano despite the obvious

With this chart we now have a living document of all the pianos which pass through the Pianodrome. It has become our piano hall of fame and infamy and we would encourage anyone who has donated or adopted a piano to come and sign a paper washer and place it on their designated peg. This can be done at the Adopt a piano showroom every Saturday 11-3:30.

However, before I get too carried away by this new innovation I have an admission to make. Nobody knows the exact number of pianos donated to the Pianodrome. We only started logging pianos systematically when Adopt a Piano started in January 2023 and used a conservative estimate of 300 pianos donated between 2017-2023 as a safe-to-assume basis. We may actually be gliding through the seven hundreds at this point, history does not record so precisely. This raises questions for us of how do we faithfully keep track of what we’ve done as we dash forward from one adventure to another? If each one of these washers is a moment in our history, how many more have gone past unregarded?

As the reassuring solidity of data has started to fray perhaps it’s better to give in to the randomness of colours rather than seek the pattern. Stepping back I can say ultimately making the Pianometer is an attempt to mark the contribution of our piano donors to the Pianodrome. Each variegated washer on the board is a token of our appreciation to all those who have helped us flourish by donating their instrument to us. The result is a vibrant, growing profusion of colour.

Washer 356 “Abbey”

Brasted

Brasted piano awaiting install.

Here is the story of one piano which has recently dropped into the flow here, tumbled over some rocks, floated under a bridge or two and now circles gracefully in an eddy; the Brasted.

Once a month since January we have been driving to Leeds in a van with a crew of Pianodromedrons to make preparations for the coming Piano Festival in September. Melvin Besbrode of Besbrode Pianos has been a great help to us, hosting us on the sixth and top floor of the historic brick and cast iron mill which houses his piano ‘emporium’ - there is no other word for it, his collection of painted, sculpted, see-through, dropped-from-a-plane-into-the-trenches-in-world-war-two pianos must surely be unique in the world.

Here, assisted by volunteers from various local planting societies, we have been pulling apart defunct pianos to make planter boxes for the Piano Trail this autumn. Melvin is a congenial host and he has more than enough pianos to spare. He calls me in advance and asks how many uprights and grands we want his movers to bring up from the vaults for us this time? Between pulling pins and bashing boards we all have lunch on the roof with panoramic views of the city and surrounding national railway viaducts.

When the time comes to return to Edinburgh Melvin opens his container of ‘maybe playable pianos’ and we are allowed to try them all and select a couple to bring back home for adoption. This is how we came across the Brasted. A gift. A lovely old upright - not good enough for Melvin to sell but a great potential fixer upper for us.

Joey Sanderson A.K.A ‘The Piano Doctor’.

As word of our project spreads further afield one of the most interesting and exciting enquiries we have had is from a wonderful pair of ladies, Rhonda and Gladys in Australia and Hong Kong respectively. Rhonda is an advocate for different gauges of piano keyboard - more specifically for narrower gauges than the, since 100 years or so, ‘standard’ gauge, which may be more suited to smaller hands - women in particular, who are currently underrepresented in relation to men at international soloist level by a ratio of 4 to 1. Rhonda, a director at the DS standard foundation, believes that narrower keyboards on pianos may remove one important structural barrier to aspiring players with smaller hands. Gladys is a philanthropist and together they contacted Pianodrome out of the blue from the other side of the world to ask if there might be a possibility to collaborate.

To cut a long story - involving various wrangles with FedEx, customs, transnational piano construction protocols and Brexit - short, Rhonda and Gladys commissioned a maker in the USA to fabricate and ship a narrow keyboard to our workshop in Granton where over the last couple of weeks our top technicians Tom and Joey have inserted it into Melvin’s Brasted from Leeds. It has been regulated and tuned and now awaits installation as one of the three embedded playable pianos in the Old Royal Pianodrome.

With its makeover complete, in a funny circular fashion, Brasted is set to return with us to Leeds as part of the Pianodrome in a few months time where hopefully lots of people will get to enjoy its even touch, full and characteristic tone and easy-to-reach keys.

Thanks to Melvin for the piano and thanks to Rhonda and Gladys for the keys.

Strings Detatched

This is a picture, taken by our very own Ant Ravelo, of almost a decade’s worth of piano strings removed from defunct pianos destined for sculpture and stored on top of an ancient Broadwood which until recently was tucked away behind a wedge in a corner out of sight and out of mind.

In preparation for our grand collaboration with Leeds International Piano Competition this coming September we moved our original five wedge Pianodrome out of our Granton warehouse workshop down the road into another much bigger warehouse with a sea view which in the coming years is set to become an upcycling hub for the construction industry called Plan A (because there is no Plan B…) In its place in our workshop the three-wedger ‘Old Royal Pianodrome’ now awaits the installation of sparkly new playable pianos, two of which will have narrower guage keyboards perhaps more suited to smaller hands.

This is a picture, taken by our very own Ant Ravelo, of almost a decade’s worth of piano strings removed from defunct pianos destined for sculpture and stored on top of an ancient Broadwood which until recently was tucked away behind a wedge in a corner out of sight and out of mind.

It had been my hope for many years to find a use for this fantastic mess. Piano strings are sharp at the ends and they have a tight curl which catches clothes and makes it virtually impossible, once a string has joined the pile, to separate it out. The bass strings are wound with copper which is 20 times more valuable than the steel core but again almost impossible to separate.

I really loved the concept Sean Logan came up with of bunches of strings making muscles to form a full size human figure, copper sinewed, trilling with sonic power. Actually I really loved this pile of strings as a thing in and of itself. Piled up high on the grand, each one containing the memory of years of musical vibration and each one a testament to the work of the hand that finally separated it from its piano, a riotous mass of chaotic energy arising from its piano plinth and frozen in time. I toyed with the idea of proposing it in its current form as a sculpture for the Leeds sculpture trail.

My heart always sinks when someone suggests taking piano parts to the dump. I feel I have failed. But I had had ample chance to make something of this mess and no idea, however inspiring, had overcome the difficulty of tidying it up. The strings were taking up valuable space and were spiky and dangerous. It seemed their time was up.

We piled them into the van and took them to the dump; more precisely the metal recycling. They gave us fifty quid and explained that rising energy prices mean that the last foundries in the UK are closing. Our strings would be sent to Turkey where they would be melted down and within 6 weeks they would become something else. The valuable copper can’t be separated from the steel, it simply becomes diluted to such a degree that it is negligible. It seems a shame. It seems also absurd that such valuable material, gleaned with such difficulty should be worth so little and shipped so far to be recycled. But what can you do?

Ant’s wonderful photo will stand as the final artistic expression of these particular piano parts.

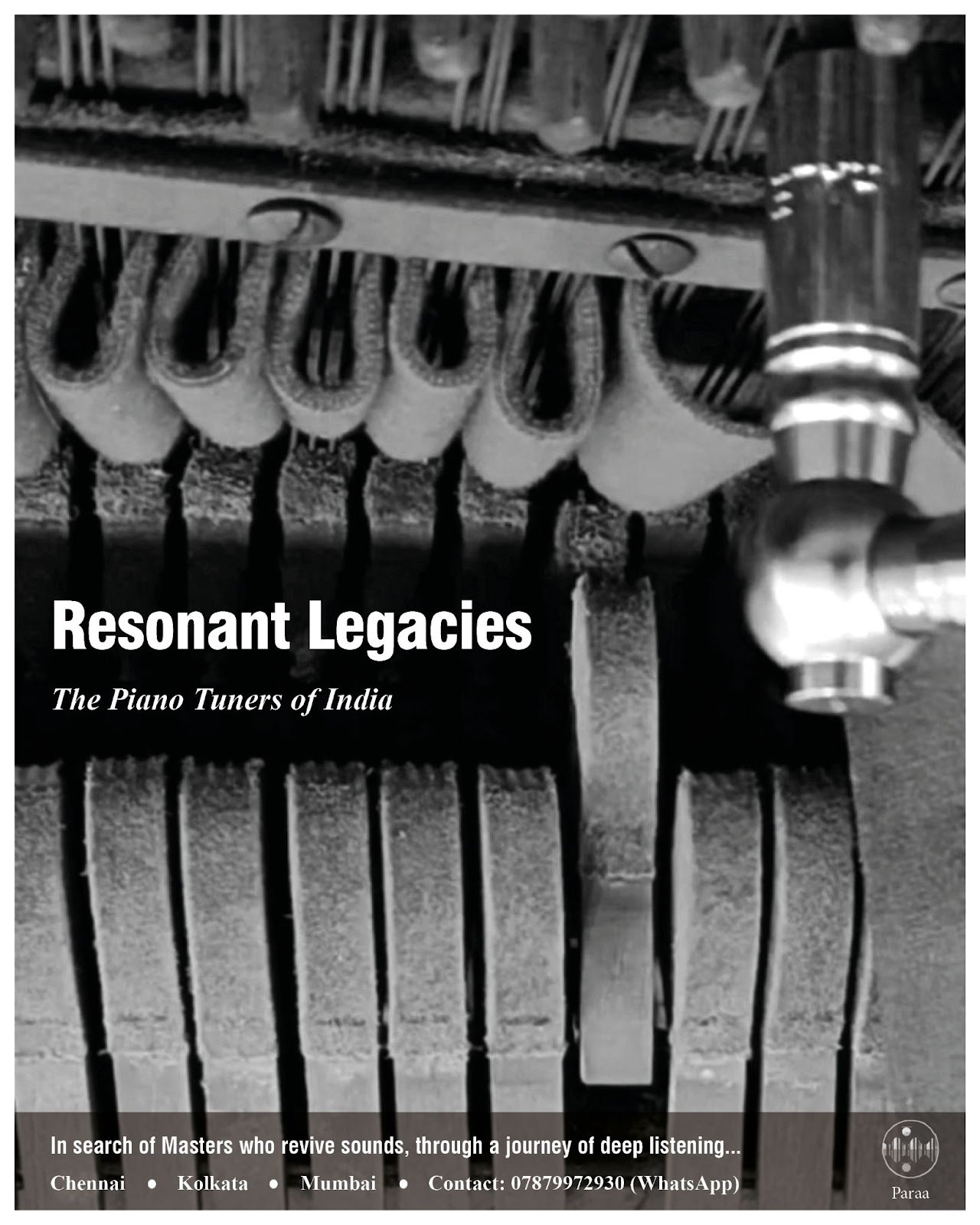

Resonant Legacies – The Piano Tuners of India

Edinburgh | “No piano is junk. No person is unmusical.”

“Hello? Hi, is this a good time to talk? I’m Mirra. I’ve been learning to tune and repair pianos here in Edinburgh and I would really like to visit your workshop when I’m in India.”

Thus began a conversation with Ajay Mistry, the owner of Mistry & Co, one of India’s oldest piano tuning and repair companies. I was nervous. I didn’t know what to expect from the conversation. I had been lucky enough to be privy to the mysterious craft of piano restoration and tuning here, but my mind kept going back to the source of this interest - an old, small-built man hunched over my piano in Chennai, intently listening to sounds I only wished I could hear.

I would take every opportunity to watch Rao Uncle tune my piano at home, especially when it meant skipping a day of school. He would strike one key repeatedly, and somehow its sound would change each time. He would ask me to play when he was finished, which I would do very reluctantly – I didn’t know why it was important for his process. I just thought he, like many adults, wanted me to play a little tune since I was around a piano. Little did I know that he was probably listening more to the piano’s sound than my interpretation of a song. With a gentle smile on his face, he would take the time to compliment my playing before returning to the tuning pins only to change the sound again. And again. And again.

By this time I had been learning to tune pianos for little over a year. And by learning, I mean following piano technician Benjamin Truehaft around on his jobs and assisting him with the little I could do. In return, he would tolerate my constant bombardment of questions – a patient teacher if there ever was one, though he doesn’t agree – and eventually even handed me odd jobs from his customers (only to go back without a fret to fix the mistakes I had made). But even this would not have been an entirely fulfilling learning experience had it not been for the hundred odd pianos at my disposal that sat quietly in an abandoned shopping centre waiting to be rehomed.

A tuning lesson amongst all the pianos in an abandoned shopping center.

In January 2023, Pianodrome officially launched the ‘Adopt-a-Piano’ initiative to save and rehome the forsaken pianos of Scotland. I was fortunate to be part of the BBC interview that launched the initiative, and I spent my free time over the next few months trying to understand and tune as many pianos that came in ( I saved up and bought my first set of tools without having the faintest idea on how to use them – thankfully, I wasn’t the only one). Each piano had a different sound and personality through which I slowly began to understand the mechanics and architecture of this wondrous instrument. Under ‘Piano Doctor’ Joel Sanderson’s tutelage, we began to learn how to bring life and love back to the pianos… And so began my time as a building conservator on the weekdays and an amateur piano conservator on the weekends.

It took mere seconds for the Pianodrome to change my life, when I did a quick Google search to find out what three different cities in the UK had to offer outside of the postgraduate education I had just been accepted to. By the end of their YouTube video featuring a demonstration on how to dismantle a piano, I was in tears. My mother was sitting next to me when I was on my laptop pouring over their website, shaken by what I was reading about the team and their work – and in a trembling voice I said to her, “Amma… Look at this. This is where I need to be.”

So I moved to Edinburgh.

By some miraculous coincidence a new Pianodrome was scheduled to be built soon after I arrived, so I spent every chance I got at the warehouse dismantling pianos and making friends. I will never forget the first time I dismantled a piano… The deconstructed sounds of strings warping as I loosened them… The calculated kick that I was taught to get the side panels of a piano dislodged from the body… I had never kicked a piano before. I had never even removed the front panel to question what was going on inside it. Every activity simply shattered everything I thought I knew about myself and the instrument. It fundamentally changed me.

My first repair job – Redoing the felts and bridle tapes on this Bechstein upright that formed a playable piano of the Pianodrome

Ben putting me to work, unscrewing the action of a grand piano

Watching Joey inspect the action of a grand piano

A pint per tuning

“Eventually Everything Connects…”

One afternoon as I was perusing Canmore to look for historic photographs of Indian architecture (as one does), I chanced upon a photograph dated 1912 whose caption read: “H Hobbs & Co, 4 Esplanade East, Kolkata, lit for the British royal visit. The shop sat next to the Military (Ordnance) Department. Harry Hobbs (1864-1956) arrived in Calcutta to work as a piano tuner …”

All of a sudden a thousand thoughts collided in my mind. Memories of watching Rao uncle tune my piano merged with the thrill and wonder I felt when I used my own tools for the first time. I had to bridge my experiences, and the only way to do that was to go back to India and meet its pianos and their guardians. So when Ajay responded to my phone call with equal enthusiasm, I knew this was going to be my pilgrimage. I also knew that finding other piano tuners in the country was not going to be as easy a task, but I had a solid place to start – I just had to go back home to Chennai.

In preparation for my visit, I released a poster calling out for leads about piano tuners and technicians in India.

Chennai | “Meditations”

The first piano I met when I landed in Chennai was my own, a gorgeous Kawai upright that had sadly not been played in a few years. I unpacked my tools even before my toothbrush and went straight to work. It felt strange seeing its shiny body, bright white keys and plastic wippens – I had become so used to aging pianos. A quick condition assessment primarily revealed sticky keys and undone unisons, a result of the high humidity in the air. That morning, I used a hairdryer for the first time.

The next logical step was to contact Rao Uncle, and also visit Musee Musical, one of the oldest music shops in the country. Going back there brought back a lot of memories; it was where I got my first violin, performed in public for the first time, and attended all three of my piano exams. Cacophonic sounds of traffic from the main road slowly faded as I walked towards a colonnaded building with tall louvred windows. Shadows of trees danced on its off-white walls. Silence. I met Somu Ji at the entrance, who, bewildered by my request to “see where all the magic happens”, took me across to the opposite newer building, up two flights of stairs, down a narrow passageway and into the workshop – which also happened to be every injured piano’s journey.

Musee Musical, Chennai

I was surprised by the familiarity I felt in a space I had never visited before. Everyone in the workshop welcomed me as their own and I felt a deep connection with the people and the pianos. Veera the resident tuner restrung a restored Scheidmeyer upright piano while two apprentices arranged the wippens of another piano to the side. Nagaraj Sir, a quiet man with a permanent hint of a smile on his face, showed me around the workshop and described their work. He had started working in Musee Musical as a driver when he was offered the opportunity to fix pianos instead. More than a decade later, he is now the head piano and violin technician in the workshop.

The team at the workshop

While we began exchanging technical aspects of our learnings from the profession, it quickly became very apparent how little I knew about any of it; and so our conversation slipped instead into a reflection of our experiences with the instrument in two vastly different parts of the world. At one point, when I described how tuning had become a sort of meditation for me as a realignment of unison from discord, Somu Ji, Nagaraj Sir and Veera exchanged glances.

“You have to meet Sachin”.

Back to the old building, up the steps that reminded me of my nerve wracking Trinity piano examination days, and out onto a landscaped terrace where Sachin and a beautiful architecture studio welcomed me into the shade. A brief introduction later, I realized I was meeting probably the only other architect and piano tuner in Chennai, if not India. We spoke about a multitude of things, from our journeys in architecture and music to Musee’s school of music and outreach programs. What will always stay with me was how he also described tuning as his meditation. The exchanged glances made sense now. I felt heard.

A few days after my visit, I received a message from Somu Ji asking when I’d return. Our conversations at the workshop had given everyone a fresh energy and enthusiasm towards their work. I felt the same way, and carried this encouragement with me to Mumbai where I finally met Ajay.

A Chernihiv upright piano (~32 years) from Ukraine waiting to be restored

I would go on to visit my school in the following weeks to tune the upright piano that was donated to them the year after I graduated (I’m clearly over it). I barely opened up the piano’s body when children gathered around me playing the keys and looking in awe as the hammers struck the strings.

“Akka, why is it making that sound?”

“Wait it’s my turn to play now, you had lots of time!”

“Can I help you clean the piano? Wait da, you take out the keys and I’ll help akka dust underneath them.”

“Akka, why is that part moving so weirdly? When I press it down the sound goes on for sooo long.”

“It’s still not sounding good. Turn it a little more akka. Okay.. Now it’s better. It sounds like one note. You can stop now.”

It took me two days to tune that piano. But those were some of my most joyous days of being back in school.

Mumbai | “Observation helps to understand. Feeling helps to realize”.

‘A Mistry & Co – Complete Piano Service’ read the board that adorned an unassuming building along a narrow street in Bycullah. Bag of fruits in hand, I stepped into the shop and immediately, all the noise from outside ceased. A 1920s Bechstein grand piano took centre stage, partitioning the room into the showroom in front and a workshop behind. Cupboards were packed with custom made piano tools that I was lucky to handle. Ajay and I exchanged our stories and briefly, our tools. It didn’t take long for me to realize that mine were sub-par, considering the even weight distribution of the levers he had. Every aspect of a piano that needed fixing had a special tool to do so.

The shop in Bycullah

Ajay’s passion for piano tuning and restoration began as a child, when he would observe his father on the job. He worked with his father for years before undergoing formal training from the Grotrian Piano Factory in Germany. While his attention to detail and the meticulous nature of his work was inspiring, I was particularly struck by the calmness with which he responded to the surprises that the piano he was fixing threw at him. There was a deep reverence for the instrument regardless of the surgery performed on it, which reminded me of the joy and respect with which we pulled pianos apart at the Pianodrome. Sounds oxymoronic, but really, it isn’t.

Ajit joined us soon after. He was studying sound engineering, and apprenticed with Ajay when he could. They had just finished a job together in Pune. Witnessing this apprenticeship gave me so much joy – I could relate the informal yet sincere nature of our conversations that day with similar ones back in Edinburgh, and it washed away the notions I had about the nature of knowledge-sharing in India. It gave me a lot of hope about continuing to follow my passion for pianos wherever I was.

Ajay adjusting the screws holding the keyboard in place while Ajit observes

The real test of my knowledge took place in the evening, when Ajay asked me to tune the middle octave of an upright piano that was quietly standing in a corner. Unfortunately for me, the piano already sounded tuned which meant I had to listen to sounds that I had never heard before. Ajay introduced me to a new system of tuning, and gave me and Ajit a short lesson on the architecture of tuning pins and their movement within and outside the pin block. It made such a difference to the way I approached my own method of tuning. I realized that I have always associated piano tuning with the act of listening alone, but it has so much to do with the articulation of movement from one’s core to the arm to the hand to the lever through to the body of the pin, and in turn the string and pin block. Observing the movement of the tuning pin and actually feeling it yielded two very different learnings. I was nervous but determined to do well. I think I did – at any rate, I was able to recognise when Ajay sneakily detuned a string ever so slightly when I wasn’t looking. A nod of approval from him at the end was more than enough.

The Bechstein grand piano that we leveled

The next day I met Amritlal uncle, Ajay’s father and the 3rd generation piano technician in the Mistry family company. This 80+ year old man regaled me with stories of Maharajas and celebrities for whom he had tuned their pianos, and jokingly chided Ajay’s new age western approaches. With the promise to teach me “the true and correct” way of tuning when I returned, he left me to my masterclass on leveling the Bechstein’s keys. When I briefly turned back to speak to him, I witnessed a scene that I’ll never forget. Amritlal uncle stood by the piano I had partially tuned the previous day, and gazed at the model cross section of an upright’s action that sat on top of it. He pressed the key multiple times and watched as one small movement cascaded into another till the hammer struck the string. This moved me immensely – even after around seventy years of experience restoring pianos, he took the time to appreciate the fundamental principle behind the instrument and observe it afresh, almost in a state of play.

Amritlal Uncle in deep thought, observing the action of an upright piano

Ajit and I were invited over for lunch that day. Purvi, Ajay’s wife, made some of the tastiest food I’d ever eaten, and our conversations around food and the intention with which we cook and eat continues to stay with me, and has changed the way I consume food. They were incredibly welcoming, and just before we left, they changed my life once more – by introducing me to the paan goli, a tiny ball of delicious magic (I found my way to Crawford Market that evening just to get some more but I didn’t find the right one. Oh well, next time.)

Ajit, Ajay, Purvi, and me after one of the best lunches of my life.

Back at the shop, Ajay took me up the stairs to see their larger workshop in the building at the back. We passed by a number of industries till we arrived at the piano workshop on the second floor. More pianos in various states of restoration.. I wondered how many old pianos were still around – I had read about S.Rose and Co. pianos, which were made especially for the Indian market by Allison and Co. in Britain and exported to Bombay. I’ll confess this line of thinking had as much to do with the capacity to restore them as it was to seek opportunities to pitch India’s first Pianodrome. As it turned out, pianos were in abundance and mostly in use. They were also largely repaired, and at whatever cost. So would a Pianodrome work in India? Maybe not in the form of a 100 seater amphitheater made out of disused pianos. But in every other way, absolutely.

Pianos in different stages of restoration in the workshop upstairs

Before I left that evening, Ajay surprised me with a brand new bag for my tools, and two muting strips.

“Come back anytime!”

Kolkata | “Sirf tuning, tuning, tuning!”

My final stop was Kolkata, home of H.Hobbs & Co. My introduction to the city’s pianos was in the form of a delicious Rachals & Co. German grand at a hotel’s lobby. I surprised myself by asking the concierge if I could take a closer look (usually I would just stare in wonder and shyness from a distance – I’ve clearly evolved). As an even bigger surprise, he said yes. I opened the lid and there it was, written in metal relief work on the harp,

“Specially made for H Hobbs and Co, Calcutta”.

I introduced myself to the piano by playing my favourite piece by Ravel and quickly proceeded to find out about the instrument and its care. It was played during special concerts, and also every evening by a blind pianist who played for guests at the hotel’s reception. It was cared for regularly as well, by technicians from Braganza and Co. I noted the company’s phone number and tucked it away, as in that moment something far more important called out to me – Kolkata’s street food.

While the H.Hobbs and Co. building no longer existed, Braganzas stood not far off. It was a dream come true to witness this old building and its instruments resonate with one another. Solid timber rafters supported a roof that sheltered the instruments held by a red oxide floor. I met Tony and Nigel, the third and fourth generation owners of the music shop, and the first thing I asked was about their experience restoring Rabindranath Tagore’s piano. What a mind-bogglingly incredible thing to do. I also learnt that they had a system of renting pianos in order to make them more accessible to people, with some rates being a bare minimum even to this day.

An upright piano on a red oxide floor – a combination I never knew I needed in my life till now.

Turning left at the courtyard I entered the violin and piano workshop, where I met Pravat bhaiyya and his team busy at work. With the little Hindi I could manage, I introduced myself and requested if I could stay in the workshop for the day and help them out with anything. Pravat bhaiyya was thrilled. He had been preparing new key tops to stick on an upright piano, but paused briefly to show me around the workshop and the different pianos being restored with parts and tools, some made in Germany and others made in the workshop itself.

The workshop, and some hand cut measuring tools

Bhaiyya was extremely pleased that my interest lay in tuning. Ajay had previously insisted that tuning was only one part in the complex process of piano restoration and that I should focus my attention equally on the repair and regulation of pianos. Bhaiyya, on the other hand, insisted that everything else about piano restoration could be picked up on the job, and that I was to only focus on mastering my tuning.

“Sirf tuning, tuning, tuning”!!

A few years ago, Max Mueller Bhavan had selected two piano tuners from every state to go to Germany for two weeks for an intensive course on the restoration of pianos, as part of an incentive to bring German pianos to India. While some people benefited from this, piano tuners continued to be rare. Most of the masters were either really old or had already passed away (incidentally, the only other piano tuner I had researched about before going to India was Mr Sisir Das in Kolkata. I could not find a way to reach him; I even tried contacting a journalist who had written an article about him. It was bhaiyya who told me that he had passed away a few years ago, and was the head technician that had trained everyone at Braganza’s).

Convinced that I was not going to leave until I had tuned a piano, bhaiyya pointed to a particularly tired one. The tuning pins were very loose and I was met with incredulous smiles as I worked my way hammering them down and tuning the strings. At one point, reflecting on my job as a building conservator, bhaiyya said, “It’s the same isn’t it, be it taking care of pianos or buildings… We just have to properly use them and care for them, and they will automatically last longer and be happy”. I didn’t have the words to respond, so with a smile and acknowledgment that swept the room, we went back to work.

Home.

Each of us settled into a work like it was second nature. One person adjusted and tuned a violin, another person buffed the keys of a piano, a third person fixed the felts on to every wippen, and a fourth attempted to tune a piano. Our own silence as we worked was balanced by our instruments in conversation with each other.

The team of technicians at Braganza’s

Over the next few hours, I was fed at least seven small cups of tea, a delicious wrap, and a seasonal traditional sweet called Moa. What a lucky day. In the evening, just as I was about to leave, Pravat bhaiyya insisted I stay put so he could prepare something. Already overwhelmed by how much they were providing me, I wondered what more they could possibly want to give.

He handed me a little blue plastic bag, inside which was a mug with our photo printed on it.

“This is for you – to remember us, and to remember to keep tuning and working with pianos. You can come back here anytime. Just walk in, and do whatever work there is. This space is yours.”

Over the next few weeks Pravat bhaiyya and I would exchange pictures of the pianos we were working on and serial numbers to figure out their age. I really want to find a way to connect the technicians from Scotland/UK with those in India. Reader, if you have any suggestions, please let me know!

Here and Now | “Tat Tvam Asi.”

I never in my wildest dreams would have imagined interacting with the piano like I do now. The instrument may still be considered austere and unapproachable by a large number of people. The Pianodrome shattered that notion for me from the get-go. The piano’s reverence is in its use and exploration. How else can children’s excitement over seeing a piano’s action for the first time be explained? What else would make a master piano technician gaze silently at a model of the action, as if he’s still learning about it?

I was called a piano technician at the Pianodrome even before I knew what being a technician meant. It instilled a deep motivation in me to learn piano service and repair to the best of my ability and share the joys and wonder of it with others. Over a phone call days before returning to Edinburgh, Rao uncle gave me his blessings to take care of the pianos I come across in my life. I’m only at the beginning, but at least I’ve started.

I am truly indebted.

~

Dear reader, I am in search of a book written by Henry Hobbs about the pianos of India. It is titled ‘The Piano in India – How to Keep It In Order’. Please let me know if you come across it. A link to a previous auction below:

https://www.storyltd.com/auction/item.aspx?eid=4590&lotno=20

Mirra’s blog: https://paraasound.wordpress.com/

The Blankest of Canvases, Adopt a Piano adventures in an ex-department store (part one)

Tomorrow we are heading into the dust shrouded remains of Debenhams at Ocean Terminal shopping centre in Leith to extract the final 35 pianos left from our time there. It’s been just over a year since Tim and Matt brought the Adopt a Piano scheme to national attention via this BBC story about saving 100 year old pianos from landfill https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-scotland-64175072

That article brought to life an entire ecosystem of pianos coming in to us to be cleaned, repaired, tuned and regulated before heading back out to new homes. Due to the success of the Adopt a Piano scheme staff and volunteers are now learning how to bring pianos back to life, revitalising a dwindling profession of piano restoration and more people are choosing to have these soulful instruments in their homes rather than a digital facsimile. That’s how things have evolved, but in the beginning it wasn’t quite so finessed.

Angus working on the newly arrived Pianodrome

The vast, empty space in the ex-Debenhams department store ground floor (lent to us by the good folk at the Wee Hub for six months or so) was the perfect breeding ground for the piano adoption scheme. Flying from its majestic roost at the Old Royal High school on Calton Hill the Pianodrome Amphitheatre touched down in the void of this abandoned, soon to be demolished half of Ocean Terminal shopping centre. The contrast was immense; a sunlit, wood panelled room had been exchanged for an all-white landscape of strip lighting, forgotten mannikins and a beep which emitted every thirty seconds from somewhere unknown.

Having sent out the call that we would take in any piano, overnight pianos of all descriptions appeared as if springing up from the beige floor tiles. I got a call from Matt to come down and help work out what to do with them. I found him deep in the midst of about 50 pianos, marvelling at the rich diversity of instruments we’d taken ownership of. Already hand written notes had appeared on several lids as people had somehow snuck in under the security shutters to reserve a good one. We roughed out a few details on how to proceed, placed a notice on social media and the website and I offered to open the showroom on Thursday to see what happens.

Potential adopters at the entrance

It was chaotic, but good chaos, and thank goodness people came to adopt our first flush of pianos. With several groups pouring over the pianos, we tried to stay one step ahead and grasp the adoption process and administration of the project on the fly. There were incredible pianos going out the door in return for any donation to the Pianodrome. The donations we received allowed us to start to fund aspects of the showroom as well as keep the Pianodrome company afloat in the lull between projects. Three or four pianos left each time we opened. Every Saturday a flurry of folk would come in seeking out a piano for their homes, during the week emails kept our administration legend Laura busy. A group of us emerged to hold the project as it grew, Mirra and Alison’s knowledge of tuning pianos was invaluable. Jonathan gave us business advice to steer the project. Pip helped with our first tentative steps towards fixing pianos and Shona worked out a system of logging our stock with Alma.

Tim wheeled out a piano to the front entrance to make a reception area and those who knew a tune took turns playing for the general public as they drifted past us towards the Royal Yacht Britannia elevator. Some tourists beguiled by the music diverted our way and followed a long, snaking line of pianos to the back of the room where the Pianodrome structure enveloped them. Word of mouth spread in Edinburgh and pianists of every ability and style turned up to play in the cavernous nowhere land of the old Debenhams, either out front, in the Pianodrome amphitheatre itself or randomly, delightfully, at a piano in some corner somewhere. The atmosphere of the room would change in an instant with the first notes of an unexpected song appearing from thin air and then transform dramatically again as a young child joined in with their first improvisational piece on another piano elsewhere.

Adoption station

In March I left for America to help build the world’s third Pianodrome and Shona, having dedicated hours of time volunteering since its inception, stepped up to run the project. I had mixed feelings about handing over the reigns. I knew she would do a great job but worried about the viability of the project. Adoptions had tailed off but the deluge of pianos coming in had not. Over 90 upright and grand pianos now littered the space around the Pianodrome structure, at this rate we were going to need a bigger department store to keep them all in. Donations could only cover the bare bones of the project, we needed to ask people to dig deeper into their pockets if we were to fully realise the potential of the project. As well as lacking the funds to work on the pianos which could be saved we lacked the knowledge to know which pianos were salvageable and which were merely decoration. Fortunately in my absence heroes emerged to move the project forward immensely. I’ll talk about them next time.

Joey and me, investigating

If you'd like to get involved with the Adopt a Piano scheme drop us an email at adopt@pianodrome.org

CO2

It strikes me as nothing short of miraculous that trees and humans are symbiotic in that we humans breathe in oxygen while trees breathe it out. The opposite is true for Carbon Dioxide (CO2). One species’ waste is another species’ resource. How about that for circular economy? It turns out that chlorophyll – the chemical that allows trees to store sunlight – is very similar to the haemoglobin in our blood. The two chemicals differ in that the iron in haemoglobin makes our blood red and the magnesium in chlorophyll makes the trees’ leaves green.

It strikes me as nothing short of miraculous that trees and humans are symbiotic in that we humans breathe in oxygen while trees breathe it out. The opposite is true for Carbon Dioxide (CO2). One species’ waste is another species’ resource. How about that for circular economy? It turns out that chlorophyll – the chemical that allows trees to store sunlight – is very similar to the haemoglobin in our blood. The two chemicals differ in that the iron in haemoglobin makes our blood red and the magnesium in chlorophyll makes the trees’ leaves green.

Haemoglobin delivers the oxygen we breathe in, allowing the carbon in our food to give us energy while chlorophyll allows trees to store energy from the sun while separating CO2 into the solid carbon in wood and the oxygen which they breathe out. Or something like that. Is that not mind-blowing? The mass of a tree comes largely from the air. Trees breathe in CO2 and turn it into wood.

In an attempt to offset our Charlotte flights, last Saturday a group of volunteers from Pianodrome planted 100 new trees at North Cloich hutting site in the Scottish Borders. One flight from Edinburgh to Charlotte produces around 490kg of CO2 so for a return it’s about a tonne.

To put this in context, the total average Carbon footprint per person in the UK including all travel, food, heating, infrastructure etc. is around 8 tonnes of CO2 per year. For the 6 return flights required to make this project happen Pianodrome produced around 6 tonnes of CO2.

Funnily enough Pianodrome Charlotte probably weighs around 6 tonnes so flying the build team over produced roughly an equivalent weight of Carbon Dioxide gas to the 40 or so pianos used in its construction. Heavy. Had these pianos been burned instead would this have produced as much CO2? But that's another question.

My question now is this: How long will it take for the trees we planted to breathe in the equivalent 6 tonnes of CO2 we produced and turn it into living timber?

Based on an hour’s googling my possibly flawed and highly approximate calculation is as follows: 6 tonnes of CO2 is roughly equivalent to 1.5t of Carbon (the other 4.5t is Oxygen). Divided between 100 trees that’s 15kg of Carbon per tree we planted. About half of the mass of a tree is Carbon therefore our trees will have to weigh 30kg each before collectively they have offset our flights. A tree weighing 30kg is around 12cm measured round its trunk. To grow to this size takes about 5 to 10 years.

On our weekly zoom meeting today Laura suggested we arrange a picnic at North Cloich to celebrate when the trees we planted have done their job of offsetting the Charlotte flights. Matt suggested we cycle there to reduce our carbon emissions on the day. So. On 22nd April 2033 you are all invited to cycle to North Cloich with us and have a picnic in the shade of our lovely trees!

One last calculation. A mature tree absorbs around 50g CO2 per day. Flying Edinburgh to Charlotte takes about half a day. To absorb CO2 at the same rate that your flight releases it on your behalf you need a forest of 10 000 trees. When I picked my 10 year old up from school today and told him all this he immediately jumped to the only conclusion I can meaningfully extract from this – we, humans, surely have to stop flying.

Familiar things

8 February 2023

So much is so familiar here – I’ve heard the accents a thousand times before, seen the Starbucks and Krispy Kremes on their imperial advance into British culture, we have motorways and car culture back home too. And yet at the same time so much is alien – endless ads on the freeway: ‘WRECK?’ ‘Life is short. Get a divorce.’ ‘There IS evidence for God.’ Who’d have thoughts to call a supermarket ‘Harris Teeter or ‘Food Lion’.

8 February 2023

So much is so familiar here – I’ve heard the accents a thousand times before, seen the Starbucks and Krispy Kremes on their imperial advance into British culture, we have motorways and car culture back home too. And yet at the same time so much is alien – endless ads on the freeway: ‘WRECK?’ ‘Life is short. Get a divorce.’ ‘There IS evidence for God.’ Who’d have thoughts to call a supermarket ‘Harris Teeter or ‘Food Lion’.

On the drive to the Harris Teeter for lunch I spy a giant brick building, maybe 16 stories high, singularly towering over a flat horizon. I ask if anyone knows about it – Greg does. Apparently it is a giant empty hotel, the Heritage Grand Hotel, which was built as part of a failed theme park. Possibly part of the reason for its subsequent failure is that this particular theme park’s theme was God. A God-themed theme park!!! Yes sireee. A local hugely successful televangelist, Jim Bakker, made millions from his TV evangelism. As the story goes, God told him that his next project shoiuld be to build a Christian theme park, and so he did. It became the third largest theme park in the world, with five million visitors per year.

Eventually though the theme park collapsed around him in a cataclysm of disasters - he was mired in controversy for drugging and raping a secretary, which began to put punters off, and then tax fraud lawsuits and a hurricane (an act of god?) which ripped apart half of the buildings on the site conspired to put an end to ‘Heritage USA’. The great big towering Heritage Grand Hotel still stands, empty and looming over the flat wide terrain, a monument to the strange and yet hugely powerful marriage of boom and bust capitalism and religion which finds a home in this part of the world.

Jim Bakker ended up in jail, serving only five years of his 45 year sentence for fraud. He got back on the horse, and now prophesise the coming end of days, and does a successful line in promoting emergency survival products.

Super Bowl

7 February 2023

Apparently the superbowl is coming up next week. ‘Oh I don’t really pay attention to it – I follow college football’ says Shawn, ‘if you don’t mind which team wins it’s just like watching a ball go back and forth in front of a camera.’ This has always been my experience with trying to watch American Football.

7 February 2023

Apparently the superbowl is coming up next week. ‘Oh I don’t really pay attention to it – I follow college football’ says Shawn, ‘if you don’t mind which team wins it’s just like watching a ball go back and forth in front of a camera.’ This has always been my experience with trying to watch American Football.

‘The half time show and the commercials are great though – that’s what you watch the Superbowl for.’ Apparently Shawn even appeared in one of these famous advertisements. If he hadn’t been living in a ‘right-to-work’ state he would have made tens of thousands of dollars from this appearance, but only earned $2,500. For saying one line.

Everything’s bigger in America

Bryan Adams and Meatloaf suddenly make more sense when you’re actually working in a big warehouse with real american guys and power tools. It doesn’t seem so cliched or inauthentic when you’re surrounded by the same accents and the same big-ness that come across in these epic anthems about desire and manly, chivalrous love.

‘Everything’s bigger in America’ - this saying is true – big cars, big meals, big pianos, big skies, big roads… and big problems.

5 February 2023

Bryan Adams and Meatloaf suddenly make more sense when you’re actually working in a big warehouse with real american guys and power tools. It doesn’t seem so cliched or inauthentic when you’re surrounded by the same accents and the same big-ness that come across in these epic anthems about desire and manly, chivalrous love.

‘Everything’s bigger in America’ - this saying is true – big cars, big meals, big pianos, big skies, big roads… and big problems. But it turns out that they have a saying here which is similar – and demonstrates beautifully the relative nature of our sense of scale. The saying here is ‘Everything’s bigger in Texas’.

The use of single-use plastic is rife here – I thought we had it bad at home, but here it’s just silly. Coffee machine pods, bottled water at every turn, wine bottles wrapped in two plastic bags by the guy at the till. I told him we have to pay for plastic bags in Scotland. I don’t think it really registered. He was impressed to learn that I was here to build an art project. ‘You must be stacked’, ‘they payin’ for your flights to get over here an everything’? At first I was at pains to say that no, actually I wasn’t getting paid a huge amount for it, but really what it came down to in the end was that I am being paid to do something that I want to do, and love to do – in that way I am stacked. I guess that’s kind of what he meant. And relatively maybe I really am stacked.

In the Kitsch-en

3 February 2023

I sit at the table – laptop out, an empy packet of crunchy granola ‘raisin bran’ awaits its transport to the recycling pile, reminding me that I don’t yet actually know when the binmen come. I’ve added another cardboard box to the overflowing pile of dry rubbish – and that will be full once the raisin bran goes in.

On the wall of the air BnB bungalow I’m staying in is a clear kitsch instruction - ‘EAT’ - the command is shouted at me in capital letters on a circular backing, made to look like it’s constructed from wooden slats, but also to look like a plate?

3 February 2023

I sit at the table – laptop out, an empy packet of crunchy granola ‘raisin bran’ awaits its transport to the recycling pile, reminding me that I don’t yet actually know when the binmen come. I’ve added another cardboard box to the overflowing pile of dry rubbish – and that will be full once the raisin bran goes in.

On the wall of the air BnB bungalow I’m staying in is a clear kitsch instruction - ‘EAT’ - the command is shouted at me in capital letters on a circular backing, made to look like it’s constructed from wooden slats, but also to look like a plate? - it is neither created ‘artfully’ from recycled wood nor is it a plate. Maybe it’s not meant to be a plate? Maybe it’s just a white circular backdrop for what someone must have thought would be an endearing word for me to meditate on whilst in the kitschen-livingroom. But I know it’s meant to be a plate because next to it an oversized spoon and fork hang from the wall – these too are reproductions, plastic I guess, and painted with a wood-grain effect to appear as though they have been hand-carved.

They are so convincing in fact that I couldn’t resist just now but to take a closer look – I lifted the fork off the nail on which it was so tenuously hung. It was heavy, weighted just like an exotic hardwood, but I could now see the brush marks, getting a sense that it was made from some kind of dense polymer. I tried to re-hang it and it dropped to the ground – of course I’ve just broken three of the four fork ends! Nightmare! Though it has proved my suspicions – behind the skin is a white, hard and brittle, almost crystalline material – it was molded after all. Ironically it will probably be almost impossible to replace – I’ll have to see what I can do with some super-glue.

This double fake is enlightening – the article provides an insight into the social environment. It seems that authenticity is no longer valued – so that the appearance of things becomes more important than the process or story behind the thing. These objects, displayed on the wall, unabashedly tell a story of creativity, bespoke endeavour, home-making, lightness and frivolity. But this story sits only on the very surface – a thin veil covering both the physical surface of the object and the metaphorical surface of my perception – just behind this film of awareness is a deeper, more complex story of extraction, mass production and acceptance of forgery. Post-truth apathy. A broken fake fork and all you can [think of is] EAT.

The boy in the laundry cupboard

2 February 2023

The boy in the laundry cupboard

We are being put up in a nice, small bungalow, with a handy porch for the car to live in. Driving is everything – my routine is car-based. There aren’t even pavements in the neighbourhood where our airB&B is based. There’s an open kitchen-livingroom and three bedrooms. When I arrived Tim was in one, but now I’m on my own – working in the days and having a few hours every evening to cook dinner, wash, catch up with emails and read or watch a bit of telly.

Two nights ago I was also doing my clothes washing when I got the fright of my life!

2 February 2023

We are being put up in a nice, small bungalow, with a handy porch for the car to live in. Driving is everything – my routine is car-based. There aren’t even pavements in the neighbourhood where our airB&B is based. There’s an open kitchen-livingroom and three bedrooms. When I arrived Tim was in one, but now I’m on my own – working in the days and having a few hours every evening to cook dinner, wash, catch up with emails and read or watch a bit of telly.

Two nights ago I was also doing my clothes washing when I got the fright of my life! The big washing machine and dryer (everything is bigger in America) are housed in a room next to the car porch, which you can only access from outside. I’d managed to lock this door accidentally last time I did the washing and the key isn’t in the house, so I had to call out the people who manage the property to get them to unlock it – finally now I could do my washing!

It was 11pm and I was in my pyjamas when I grabbed the torch and went outside in the dark to fetch my nice clean washing. I opened the door with my eyes down and there in front of me was a mobile phone – it wasnt’ mine, and in my confusion I thought it must have belonged to the handyman. Strange – I picked it up and reached to open the door of the dryer. As I brought the light up I suddenly noticed there was somebody curled up on top of the dyer! A sudden fright – with 100 things passing through my head at once… then a doubletake. There was definitely someone sleeping on the dryer. They were crunched up awkwardly, using a box of fabric softener as a pillow.

‘Errrr, hello?’

Shining my super-bright torch into the space in front of me, the details of what I could see started to emerge. A curled up youngish man in a light blue jumper, matching trousers and multi-coloured silvery trainers – the whites of his eyes opening reluctantly, and a white spittle in the corner of his mouth.

‘Hello? Are you OK? Can I help?’

It took a while before he answered – with a murmer. His eyes were circling and his tiredness was clearly fighting to keep him asleep. I offered him some water, and told him that I’d just found his phone on the floor, which roused him. I brought in the water and I noticed the sour smell of someone who hasn’t changed their clothes for a long time and has been sleeping in corners. He was clearly scared, but didn’t want to go anywhere else, and was saying that his phone was dead and he hadn’t been able to charge it. Then I offered him some food and he said yes – he hadn’t had anything to eat since the morning.

I went back in to the house to heat up some pasta in the microwave – and had a moment to assess what the hell was going on. After the initial jolt of fear I recognised that this boy had possibly been more scared of me with my bright bright torchlight and my strange accent. I’m in America, so he could have a gun… but I guessed that if he was going to hold me up or steal something he wouldn’t be just crashing out in the washing cupboard. Anyway, I went back to him with the pasta and handed it to him. As he started to figure out the food, sitting on the washing machine, I started to get a sense that he was just really in need. I had to face up to my prejudices – could I really invite this random person in to the house? Would he steal everything? There’s an iPad in there…. Etc.

But what else could I do – I felt mean awkwardly standing there watching him eat while hunched over, sitting on the dryer. Calling the cops in this context could literally be a death sentence! I considered making a comfy space on the laundry room floor for him – but there are two spare bedrooms in the house. It began to dawn on me that I might be about to offer him a bed. At the very least I could let him inside to eat.

I told him he could come and eat at the table, but that he would need to respect my stuff. He agreed to come in. He was really hungy. While he was eating he told me that he had been thrown out by his mum. ‘I shoulda seen it coming’ he said a few times. He told me his name was Chris, and that he was 23. He was thrown out 8 days ago. I don’t think we was on drugs – he’d just been left out in the cold, wandering the neighbourhood and his mobile was completely out of battery.

When I told Chris I was here to build a Pianodrome he said ‘I was kinda in to that kinda thing at school’. Instead it turned out, he works in a ‘sub’ shop making sandwiches, and he was working there tomorrow. To prove it he showed me his cap. ‘I can’t see this being my career’ - ‘my manager is happy with it, but it doesn’t work for me.’ I noticed a tatooo on the back of his right hand – I asked him to show me and he pulled up his sleeve: ‘Self-made’ he said, showing me the black cursive lettering across the back of his hand. He has four siblings, a couple of them older, with families and a younger brother just starting college. It sounds like his mum had just got fed up with him still living in the house and had kicked him out finally.

He wolfed down the pasta, which he complimented, especially the ‘cheesy bits’ and then suddenly got strong stomach cramps. At that point, cliutching his stomach he looked scared, until I reminded him that if you don’t eat for a while and then eat quickly that’s what happens. Maybe he thought for a moment that I had poisoned him? Of course he just needed to lie down and digest.

I started to realised that I was going to offer him a bed – there is space in the bungalow, and why not? I didn’t feel threatened, but it did keep my mind occupied throughout the night. I offered him a shower and a bed – but he was clearly uncomfotable and just sat on the sofa. I told him to lie down, which he did – and closed his eyes, and then in a short moment he was asleep. I covered him in a blanket and went to bed – not until after I had gathered a few valuables and taken them in to my room for the night. I told him I’d be getting up early to go to work, so we’d be leaving the house at 8.

The next morning he was on the phone when I arose – to his 2 year-old daughter and her mother it turned out. She was staying with her mum who was not willing for Chris to stay with them either. I made him some breakfast - bran flakes (in this country they are covered in a film of sugar), he commented about them being the kind of ‘healthy’ food that that his mum eats – then he took something like a 40-minute shower, came out and poured the breakfast into the bin cause it had gone soggy. By this time I was eager to get going to work, and had been trying to get him to wrap things up and leave for an hour or so. I suddenly got a sense for the kind of frustrations his mum might have been challenged with which might have led to him being chucked out.

I got his number, we said good bye and he left the house. I had a good excuse for being later than expected at the workshop.

The first Pianodrome Charlotte volunteer day

31 January 2023

Today 9 volunteers turned up to get stuck in to taking apart pianos - it was an amazing experience to share what we know so well from back home, and to find such enthusiastic and like-minded people so far away.

31 January 2023

Today 9 volunteers turned up to get stuck in to taking apart pianos - it was an amazing experience to share what we know so well from back home, and to find such enthusiastic and like-minded people so far away. The group was really diverse and really reminded me of the kinds of turnout we get in Edinburgh when we run these kinds of events. There were of course differences. Around half of the people who were there work in the city - and that means essentially working in banking or insurance. Shawn brought a huge box of Dunkin' Donuts along.

It’s Krispy Kreme’s! Photo credit: Matt Wright

And we discovered an amazing sawdust pattern which came out the back of one of the pianos which had been dismantled. The patter shadows the ribs of the soundboard - all the sawdust which had accumulated in the back of the soundboard dropped out on the floor when the piano was turned around, forming this amazing hashed pattern. But the really cool thing we noticed was that there were a few large empty circles in the pattern. These corresponded to much smaller holes in the soundboard. I realised that these must have occurred when Dray was working on removing the bridges - these need to be tapped out with a combination of paint stripping spades and wooden wedges. This continued banging will have been vibrating the soundboard, causing a pressure change inside the cavity underneath and, like the hole in a subwoofer, pushing air in and out of the hole as it resonated. The air coming in towards the floor will have blown little puffs of sawdust away forming these large clean patches!

Photo credit: Matt Wright

Up the Interstate 77 to Charlotte

27 January 2023

The sun shines on the accumulation of tower-blocks that is Uptown Charlotte as I drive up the freeway – the Interstate 77. Charlotte is a banking boom-town – steadily growing through aggressive gentrification over the last 20 to 30 to 70 years. Almost everyone I meet has arrived as an incomer from somewhere else in the States.

27 January 2023

The sun shines on the accumulation of tower-blocks that is Uptown Charlotte as I drive up the freeway – the Interstate 77. Charlotte is a banking boom-town – steadily growing through aggressive gentrification over the last 20 to 30 to 70 years. Almost everyone I meet has arrived as an incomer from somewhere else in the States. I have heard a couple times from proud locals that Charlotte is the second biggest banking centre in the US to New York. I’m heading in to town for a meeting with donuts to discuss programming with Robert Krumbine and Tim Scott, Robert’s ‘main music guy’.

We're building America's first Pianodrome in this unlikely skyscraper - this place is obsessed with newness and gentrification, and the city has a history of essentially clear felling old parts of town to make space for big new developments. Hopefully we can create a living example of what can be achieved by taking a different kind of attitude towards materials and people, one where we acknowledge how much we already have, and where we work with what is already around us.

Pinblock Mantelpiece

What is the most aesthetically pleasing part of a piano?

Perhaps it is the iconic keyboard, with its ordered universe of black and white keys, either shining brightly or showing the tallow use of decades of enjoyment? Could it be the keyboard lid which seamlessly curves over the keys, closing to meet a miniature lock and key? Or maybe it’s the front panel adorned with decoration; either embossed with elegant beading or inlaid with marquetry depicting dreamlike flower scenes or astral forms? There is much to love in the piano’s pleasing form.

What is the most aesthetically pleasing part of a piano?

Perhaps it is the iconic keyboard, with its ordered universe of black and white keys, either shining brightly or showing the tallow use of decades of enjoyment. Could it be the keyboard lid which seamlessly curves over the keys, closing to meet a miniature lock and key. Or maybe it’s the front panel adorned with decoration; either embossed with elegant beading or inlaid with marquetry depicting dreamlike flower scenes or astral forms. There is much to love in the piano’s pleasing form.

For me though the most beautiful part is hidden away, only revealed once you have completely taken a piano apart. By removing all of the outer panels, the keyboard and key shelf, unwinding all the strings, taking out the pins and finally detaching the cast iron harp you are left with the skeleton of the piano; timbers stretching from the base upwards connecting to the pinblock running along the top. This pinblock or “wrest plank” is the piano’s hidden gem.

Whilst the outer panels are polished to a high sheen the pin block contains an unadorned charm. Stamped with the serial number of it’s maker, there is a spinal sweep of holes cascading from left to right. Once these holes housed the pins on which the strings of the piano were wound. Now they form a complex pattern which, in it’s seeming irregularity, only hints at their original purpose and brings to mind insect burrows or tactile punch card holes.